Dark arts, grey areas and other contingencies

Abstract

Drawing on the dark arts, the domain where magicians and fortune-tellers commune with unknowable, faceless entities, we explore economic and cultural grey areas to reclaim tools of business administration as an artistic medium.

The text is adapted from a lecture performance by Maja Kuzmanovic at RADMIN: Festival of Administration on 15th February 02019

Full text

Disclaimer: This article discusses works and techniques that are often frowned upon in our techno-materialist society. So if some of this content appears dubious, feel free to substitute our words with others that you might feel more comfortable with. Magic, for example, can otherwise be referred to as “advanced technology”. Those who resonate with baroque ceremony may be comfortable with spirits and spells, while those of you who align yourselves with more pragmatic lineages might prefer naming these things “clear mind” or “prayer” or “contemplation”. And for the more hardline rationalists or skeptics, you can consider this session as an experiment in meta-belief.

Diving straight into the deep, we’ll begin with a quote from the introduction to Magick in Theory and Practice.

“In this book it is spoken of the Sephiroth and the Paths; of Spirits and Conjurations; of Gods, Spheres, Planes, and many other things which may or may not exist. It is immaterial whether these exist or not. By doing certain things certain results will follow; students are most earnestly warned against attributing objective reality or philosophic validity to any of them.” — Aleister Crowley

Lightening the load

In a world enthralled by market economics… sooner or later every artist is faced with the existential question: How do I finance my work? Day jobs? commissions? government funding? direct sales? a gallerist? the informal economy of the precariat? Most of us end up grappling with some combination. Whatever form the financing might take, it almost always requires some engagement with bureaucratic institutions or profit-driven corporations and individuals.

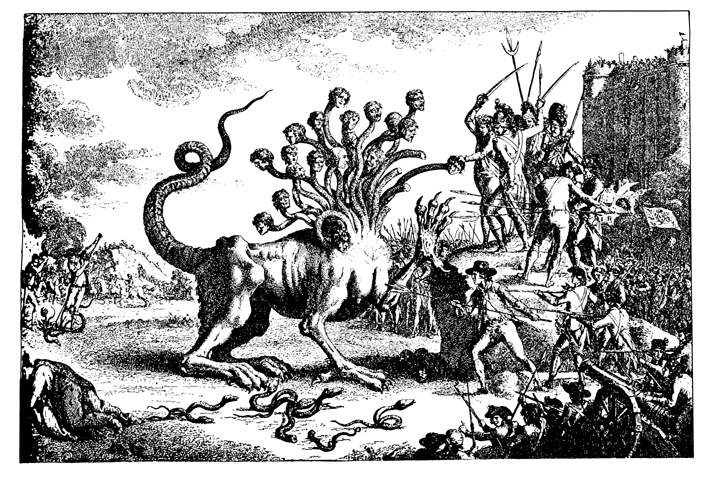

Over time, such engagements can gradually infiltrate all aspects of our work. Business administration has spread through other domains like a plague of zombies, or hungry ghosts. In its wake crawl hordes of burnt-out, semi-living artists, scientists, academics, SMEs and miscellaneous members of the cultural proletariat. Researchers who spend most of their time complying with bureaucratic procedures instead of conducting research are unfortunately all too common. Artists who become so overworked by endless fundraising that they have no energy left for creative work. Social entrepreneurs whose business acumen is overrun by the red tape involved in transparency and accountability.

Rather than allowing administration to infect our creative process, how can we keep it in check? How do we imbue it with something like the ideals from Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millenium — Lightness, Quickness, Exactitude, Visibility, Multiplicity and Consistency? Lightness could be encouraged with seasonal purification ceremonies known to substantially reduce paperwork. Business plans should stimulate imagination by bringing visions into focus. The multiplicity of bureaucratic regulations could work together, like alchemical techniques leading to the union of opposites. Quickness and exactitude of accounting could be improved. Regular banishment rituals could make overly complicated procedures more consistent.

Estonia provides a good example of a nation state reducing bureaucratic inertia in much of its public administration. Through the Digital Nation initiative they are simplifying administration where possible and automating where appropriate. They are attempting to decentralise the financial system and creating protocols for exchange between previously unconnected entities. Most importantly, they are involving their citizens in the process, without hiding behind opaque regulations and complex technologies. According to their National Advisor, Marten Kaevats “The main reason to start this discussion now is that the Estonian public administration feels that these challenges are imminent, and we have to be able to discuss them in our kitchens and saunas and with our e-residents around the world.”

Admin Craft

How could we reclaim tools of business administration and realign them with more inclusive ethics and an aesthetics of generosity? Can we increase the probability of success through the numerology of creative accounting? What promising ways could we imagine of transmuting administration into a creative practice?

First of all, we have to acknowledge that we cannot escape administration. We can try to fight it, but we will likely lose. Resistance is futile. Whatever we do we must not freeze, blocked by fear of a complicated spreadsheet. Instead, we can try to calmly attend to administration, while keeping a tight watch on our own boundaries. Administrative work could be practiced as a detached, out-of-body experience. Techniques used for lucid dreaming can help in moments when we get swept up by the strange inner logic of administration. Alternatively, you could try administering things in a gnostic state, to bypass conscious thought and objective truths. Or you could look at your paperwork through the eyes of a Zen monk.

Here is a meditative exercise for you to try when feeling the mental squeeze of administration.

Make yourself comfortable, stretch out a bit if needed. Then close your eyes or lower your gaze without focusing on anything in particular. Take a few deep breaths — count to five for an inbreath, five for an outbreath. Then let the breath resume its natural rhythm.

Bring to mind a situation in which you do paperwork. Notice what is around you. Perhaps a computer, some filing folders, stacks of receipts, or whatever else comes to mind. Notice the contact of your body with your office chair or the floor. What do these materals feel like? The smooth texture of printing paper, cool spikiness of paperclips? What can you hear? Clicking of the keyboard, shuffling of paper, the whirring of a shredder… something else? What does your office space smell like? The scent of paper archives, or freshly cleaned floors, or the slightly plasticky waft emanating from hot computers?

Breathe and observe… Notice what effect this situation has on you. How does your body feel — your shoulders, throat, chest, your hands or your belly? Is there some tightness, cramping, squeezing? Breathe into this tension. Try to soften, relax the sensations that feel too constrained. What thoughts arise? What emotions? Watch them come and go, without grasping. Without resisting anything. Now let the whole situation dissolve in your mind’s eye, until your breath fills your attention.

Breathe, in and out. Occasionally remind yourself to stop planning and return to breathing.

You can do this exercise for a few minutes, stretch out a bit, perhaps using some “administrative postures”

Know that whenever you feel in the grip of uncomfortable administrative tasks, it can help to pause and take some distance from it. Whether by using meditative techniques, going for a walk, enjoying a cup of tea. One of the proven methods at FoAM is to put on headphones, play some loud black metal (or other energetic music to your liking) and/or dance like a banshee for a few minutes.

When engaging with administration, we must always remain aware of its insatiable urge to swallow every precious minute and every unclaimed bit of headspace we don’t insulate from it. Administration must be confined to heavily guarded summoning grids; to protect ourselves and our loved ones from its ever expanding, time-sucking appendages.

You might wonder — why would I engage with administration at all if it poses such an existential threat to my wellbeing? Because as much as you’d like to pretend that you cannot be touched by it, administration is always and already here. If you want to be paid for the work you do, you necessarily engage with administration and financing. They have insinuated themselves into most of our conversations. Oscar Wilde was onto something when he said “When bankers get together for dinner, they discuss Art. When artists get together for dinner, they discuss Money.”

We commiserate. We complain. We blame, and occasionally wallow in despair.

What, or what can we artists do…

When handling financial instruments feels dangerous?

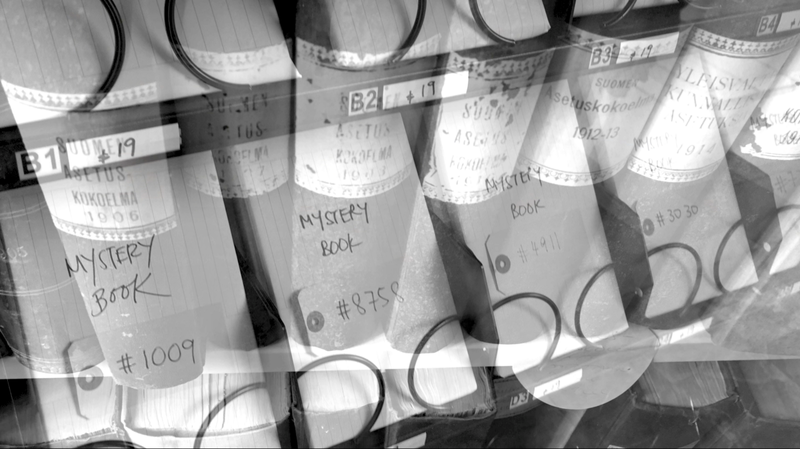

When funding applications read like incomprehensible occult texts, and accounting spreadsheets are as undecipherable the Kabbalah?

When the language of funding appears too obscure, impenetrable, as if fuelled by a hostile alien logic?

Considering that many of us depend on some form of funding for our livelihoods, funders can seem to acquire supernatural powers over life and death.

Engaging with such faceless entities beyond our control — yet with ability to change the course of our lives — was traditionally the domain of dark arts; of magicians, witches and fortune-tellers. They know that the entities they’re engaging with are not innocuous. They also know that communing with these entities has the power to transform lives and sometimes reality itself. There are similar Entities in the economic sphere. Binding ourselves to them can be as dangerous as practicing black magic. We already know that if we don’t consciously engage with administration, its effect on our practice and its consequences for our lives can be far reaching. We must therefore approach administration with a high degree of care and with all the protections that we would use when summoning an otherworldly daemon. Especially when administration is our subject of experimentation.

So could the tools of the dark arts help us engage with the bureaucratic and economic strategies deployed around us? Or, if we want to go a step further, how do we consciously engage in the manipulation of reality through administrive activities? There is a whole range of techniques from magic, alchemy, religious rituals and other occult practices, that can be applied to different aspects of administration and financing. Let’s take funding and divination as an example.

Fundraising as divinatory practice

In fortune telling and divination, great attention is paid to crafting clear and powerful questions. You don’t want to mess things up by asking a question that could be misunderstood by the entity or entities you are communing with. So before engaging with a funding agency, know well what it is that you want to ask. Prepare yourself to be in the right frame of mind. Then divine the most auspicious time and place to engage with this particular entity. Know what you are asking for, to understand what’s on the cards.

First, acquaint yourself with the entity’s traces in consensus reality. In this case, Funding Calls; Programme Frameworks; Funding Criteria and Thematic Priorities. For some of us reading these documents closely might cause nervousness, panic or self-doubt. Instead of burying yourself in the details of bureaucratic minutiae, it might help to call on the arcane technique of scrying. Scrying traditionally includes gazing into crystal balls, candles, entrails or tea leaves. Scrying with funding documents allows you to get behind the jargon to uncover hidden meanings. Scrying facilitates an intersubjective scanning of an application form. You can reach towards the minds behind the document and ask them directly what they really want from you, and what are the real costs of engagement. Scrying requires you to let go of your resistance to the material, to let go of prejudices, fixations and expectations. Until you can function as a medium, able to commune with the spirit of the funding call.

During scrying your mind is highly alert, yet open and relaxed enough to be able to read between the lines. Scrying can feel like staring at the “magic eye” stereograms. In order to see the three dimensional image in a two dimensional texture, you mustn’t focus on the surface. Instead, you have to relax and unfocus, so you can glimpse the image embedded underneath. When you’re fully absorbed in scrying you can uncover the synchronicities between the funding demands and your own needs.

When it comes to writing a funding application, we do not have to dig deep to find its kinship in the dark arts. Applying for funding is obviously a form of invocation. In any invocation, the force of intent is directed to convincing forces beyond our control to help with a given predicament. This could equally be a divinity, a spirit, or a disembodied many-headed bureaucracy. We invoke one or more of these entities to assist us in a conjuration of resources, within ourselves or in the world. A prayer is a form of invocation, as is a spell. The purpose of both casting spells and fundraising is essentially extraction of favours from a fiickle universe. We ask for favours because we cannot achieve something on our own, Be it unrequited love, gold at the end of the rainbow or money to develop an art project.

If you happen to be writing a funding application, try focusing all of your intent into communing with the institutional spirit that lies within. Frame your intent in clear language. When you cross the threshold into the magic circle of application writing, commit yourself fully. Focus. Monotask. Like skilled readers of tarot cards, use language that is ambiguous enough, yet not too vague, so that it conveys what you want to say in a way that the funders want to hear. Concentrate your energy in well a delineated Time and Place.

Believe that force of your intention will steer your proposal towards higher probability of success. If nothing else it will be more enjoyable than if you approach proposal writing as a boring necessity. Do your best, then let go. Even the most skilled invocations are not in control of the outcome. Trust that whatever happens will contribute to your liberation. If you are successful, you will have the freedom to develop your work with more resources. If you aren’t you will strengthen your capacity of improvisation and resilience while being free to pursue other oportunities. And if it doesnt work, don’t give up. Restart the cycle — reframe your question, scry the context, invoke your intent, summon your helpers and apply yourself to the process with abandon, yet without attachment to any particular result.

When you’re done, you might consider making an offering, to underline your commitment to the reciprocal relationship between you and the funder. This could be a thoughtful binding of the application package. A well designed front page. A kind word in the cover letter. Or a symbolic wax sigil on the envelope.

When the application is submitted, it is time to ritually close the circle. Pack all the paperwork away, cleanse the space of any residual proposal language, then celebrate. Do not forget to hold a celebration every time you submit an application. Even if it is just stopping for a few minutes to toast to all of the human and beyond-human entities who were involved in the process. A celebration will help you cross the treshold back into your everyday. Also ensure that every time you receive a result, no matter if it’s positive or negative, celebrate again. As a token of gratitude, to yourself and everyone involved. Remember to never take the funding for granted.

If successful, the reality you want to invoke will become legible to the funders, who in their turn might become enchanted into giving this reality their blessing. And if this happens, you can unabashedly call yourself a mage of chaos magick. Chaos mages use techniques from a wide range of occult systems. They experiment with applying them in different contexts, while remaining aware that the techniques are effective due to the belief of the practitioner. You believe that by submitting a funding application there is a chance that your life will improve. The funding agency believes that if they approve your report you have done everything according to their rules.

If we look at funding and administration not as vehicles of absolute truth, but as manifestations of a particular belief system, we might give our sense of agency a boost.

Working with grey areas

Let’s zoom out a bit to observe the wider economic realities that have shaped the current guise of funding and administration. Economies can be seen as specific kinds of belief systems. These economic beliefs are encoded in legal statutes, financial conventions and patterns of behaviour. You believe that if someone give you pieces of paper or metal named “pounds” you will be able to exchange it with someone else for a sandwich. Most of us engage in this most straightforward economic exchange — buying and selling — without much thought. By trusting that we can use money to support our livelihoods, we become complicit in maintaining this particular belief system, reinforced by governments, central banks and international markets.

Contemporary economic actors also deal in more oblique strategies, including offshore finance, complex derivatives, or blockchain based autonomous organisations. There are creative accounting practices with seemingly harmless names like the Double Irish, Dutch sandwich or Single Malt. These strategies inhabit or create legal and ethical grey areas.

Grey areas can be seen as places where different beliefs about how the world should work overlap, interfere or create gaps. In grey areas fixed rules dissolve into edge cases. They point to flaws in existing systems. They allow economic outliers to emerge from a legal limbo. They can become a temporary refuge to those of us whose lifestyles don’t always conform with consensus reality. Artists working with communities across borders. People working between monetary and non-monetary economies. Migrants who fall between the gaps of national tax regimes. To name but a few.

If you’re interested in operating in grey areas, you need to remain vigilant. Rules and regulations keep changing, so what might be perfectly legal one day, could be a definite no-go zone the next. But, if you are comfortable with a degree of uncertainty and enjoy being somewhat adrift, grey areas can be fertile grounds for experimentation.

Let’s look at a specific example. Most of us have heard about offshore finance. In it’s simplest form, offshore finance means transferring payments, debt or fees between legal entites in low tax or low administration jurisdictions. It’s called “offshore” because of the historic prevalence of islands who attracted business to an otherwise resource poor region (e.g. Panama or Malta). However, there are also landlocked countries in the middle of Europe, like Luxembourg or Andorra who are also considered offshore centres. Most entities who use offshore finance do so to avoid administrative or financial obstacles that exist “onshore”, in their home juristiction. It’s most commonly associated with secretive investments, money laundering and tax avoidance by criminal sindicates, corrupt politicians or oportunistic multinationals.

Tools like offshore finance are not necessarily limited to international companies in the Channel Islands or Bermuda. British charities use complex financial instruments to facilitate work in disaster areas or war zones. The companies managing royalties for The Rolling Stones and U2 both share an address in Amsterdam’s Herengracht. Working in economic grey areas can be interesting for different reasons. What if you could use some of these instruments to pay your collaborators who are unable to get work permits in your country? Or if you could facilitate sharing of infrastructure amongst distributed collectives? What if you could reduce administrative complexity? What current obstacles that you are facing could be overcome with experiments in the grey areas of global finance?

One of the most peculiar grey areas emerging in the last decade has been the rise of cryptocurrencies and public blockchains. What began as a sparkle in the eyes of a few self declared cryptoanarchists has captured a small (but significant) shard of the popular imagination. Cryptocurrencies are decentralised, peer to peer digital cash systems. They enable transactions between people without the need for trusted third parties (such as a bank or a state). Such transactions are now more-or-less accessible to anyone with a smartphone.

It is currently possible (with some initial effort) to transfer “money” to anyone connected to the internet in a matter of minutes and for only a few cents. This transfer does not have to be authorised, vetted or approved by a central authority. Since these systems are still in their infancy, their all have certain quirks and disfunctions. And yet, they are quite convincing sketches for a more decentralised global financial system.

Contemporary cryptocurrencies began their rise in the wake of the GFC in 2008. This was a time when the institutions to whom we entrusted our hard-earned “money” let many people down. After this massive “crisis of confidence”, unsurprisingly, many people began searching for alternatives. With cryptocurrencies trust shifts away from state institutions and banks toward supposedly impartial, decentralised, heavily encrypted digital systems. By extension, we also place our trust in those who are programming it, or attempting to attack it. It is therefore crucial to engage with programmers, computer security experts and other blockchain wizards to ensure that the systems they are building remain as inclusive as they promise to be. It will be interesting to observe what happens at the interface between the digital and local economies, between people and the trustless technologies that the blockchains rely on.

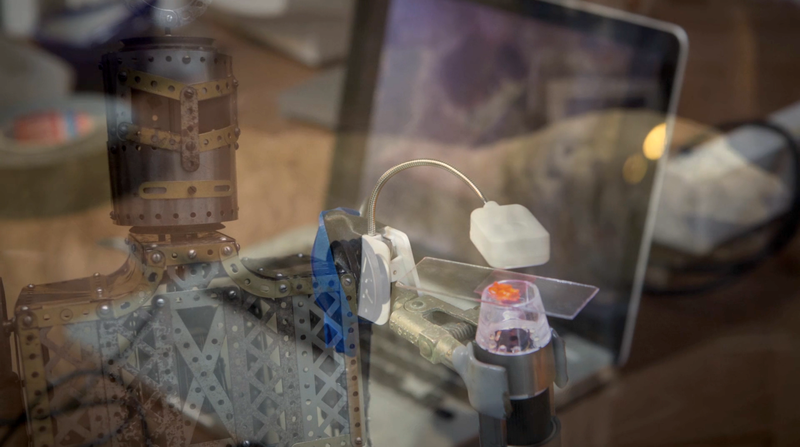

Blockchains can provide insight into a grey area where machines are beginning to gain agency in economic transactions and other aspects of daily life. From self-driving cars to e-governance, technologies are emerging to perform tasks and make decisions on our behalf. While we may be relieved to outsource paperwork to AI administrators, what might be their hidden costs?

Estonia again provides an excellent example of discussing emerging technologies in the public sphere. Their willingness to involve civil society in technological policies is admirable. For example, there is a recent discussion around algorithmic-liability laws, which is often too abstract and complicated for most of us to understand. So instead of wrapping the whole issue in techno-legal jargon, they drew on Estonian folk tales.

A kratt is a magical creature, well known to Estonians from their mythology. The kratt is a creature made from household objects, who is given a soul (by the devil). Once it acquires a soul, the newly animated kratt will take on any task it is given. However, it must be constantly put to work, otherwise it becomes dangerous for its owner. So the greedy or lazy owners end up devising increasingly impossible tasks to try to get rid of the creature. As you can imagine, this usually goes very wrong. The kratts have been known to self-combust and burn down houses, for example. The kratt stories warn about the hidden costs and responsibilities of engaging with beings and processes capable of affecting the world on our behalf.

Complex technologies such as AI and machine learning are increasingly involved in our economic and governance systems. They will likely generate a multitude of grey areas that we can’t even begin to fathom yet. Grey areas that could bypass humans alltogether. We already have technologies to assist landcapes in becoming co-operatives, rivers which can act as legal entities. terra0, for example, an augmented forest that owns and utilises itself. In this grey area we’re looking at the birth of exonomics, a field focusing on what were traditionally seen as economic externalities, like clean air, the wellbeing of a microbiome or the beauty of the atmosphere. Soon we may be studying animist exonomics alongside free markets, modern monetary theory or steady-state economies. Here too we might have to call on techniques from the dark arts, shamanism or animism to be able to commune with “planetary others”.

Whether you believe in other-than-human sentience or not, we can explore the idea of a multispecies, animist exonomics as a proposition. A lure for feeling a world that might be… A world in which everything is animate and engaged in reciprocal economic, social and cultural relationships.

Imagine yourself in a time and a place in a not too distant future, when animist exonomics is the stuff of everyday life… You are at home, working. Where are you? What does your home look like? Where is your home? If there are windows, what can you see outside, what are the surroundings like? Who are you? What do you look like? What are you wearing? What is your body posture? Are you sitting, standing, lying down, moving? What are you doing? What is your work? Are you working to live or do you live to work? Do you work alone or are you surrounded by your collaborators, human or otherwise? How are other entities engaged in your work? What do they look like? How do you communicate with them?

Does your work support your livelihood? Is there money in your world? If so, what is the role of money in your life? If not, what is valued, what is exchanged? Now imagine that you have only a month left to live in this world. What would become important? How would you spend this last month? Who would you be with, work with, share your life with? What if you had only a few minutes of life left in this world? What would you really care about? What would you want to take with you, if anything? Where are you and who are you with? What matters?

Remember that you already exist in multiple worlds. There is no clearcut dualism of black and white, us and them. All of us exist in grey areas. The sum total of our actions consists of many shades of grey, many shades of shadow.

RADMIN and the precariat

In our struggle to survive neoliberalism or consumer capitalism we may cross lines defined by our own ethics. You can expect that you will continue to be confronted with ethical dilemmas. You will have to straddle different beliefs and worldviews, because there is no single, clearcut way out of the convoluted circumstances we live with today. It’s becoming essential to increase our economic literacy. If for no other reason than to demystify strategies corporations and institutions deploy on us. Or, as a more tactical approach, those of us operating on the fringes of mainstream economies can re-mystify existing financial instruments. By conducting experiments with alternative forms of exchange.

Most artists engage in some form of informal economy. Where simple monetary transactions become muddled, entangled in a complex ecosystem of different types of exchange. While teetering on the edge of poverty or making do with lower-than-minimum wage is still seen as part of the archetype of a struggling artist, things become complicated when there are families and collaborators to take care of. In many collectives, co-operatives, networks and intentional communities economic exchange often happens in-kind, through some form of barter or favour trading. Some of these entities incorporate into organisational structures, to be able to interface with more mainstream economies. Some experiment with organisational structures themselves, as part of our creative process. The experiments vary in organisational shapes and sizes, depending on time, people and available resources. While co-creating and co-organising economic entities of our own making feels empowering, it also requires straddling different worlds. Shapeshifting from one world to another, speaking their different languages, being pulled in different directions and challenged to overcome violent attacks, insecurity and self-doubt.

Our dedication to a cause or a movement can lead to an escalation of commitment. We can perhaps allow ourselves to fail, but not to give up. Most of us have probably experienced self-exploitation, resulting in some form of burnout or other work-related illnesses. Not knowing how and when to give up can also lead to other losses that economists are very aware of. The sunk cost fallacy, for example, explains the difficulty of giving up a project due to the amount of time and resources that have already been invested in it. Even when the outcome is becoming increasingly dubious. Even if it would take much more investment in the future to possibly make it work. And while we keep on with the drudgery of this hopeless project, our opportunity costs are mounting. The hidden costs of missed opportunities, of all the things that we didn’t do because we were too busy escalating our commitment.

“I can’t help but worry” says Anna Tsing “when the scrap metal will run out, and whether there will be enough other stuff in the ruins to make continuing survival possible. And while not all of us enact such a literal figuration of living in ruins, we mostly do have to work within our disorientation and distress to negotiate life in human-damaged environments. Without the singular, forward pulse of progress, the unregularized coordination of salvage is what we have.”

And yet, we know how to work with contingencies. All of us still wake up and and get to work on things that we believe are good, without any certainty of success. Whether we run co-operatives, host workshops, create artworks, teach, learn or play. Working with RADMIN isn’t easy, but it is worthwhile.

If you find yourself in doubt, call on Calvino’s guidance. He’ll remind you that you can bring lightness to paperwork, by removing all of the unnecessary details and formalities. If you are stressed by deadlines, know that quickness does not always mean speed, but finding an appropriate rhythm for each of your administrative tasks. Administration, like writing, demands exactitude, clarity and meticulous preparation. The more prepared you are, the more effortless the work will be. If you’re frustrated by administrative rules and regulations, see them as creative constraints that prevent you from getting lost in the vastness of possibility. If administering and accounting feels dry and boring, try to see them as parts of a larger whole, that connects to a multiplicity of tasks and people.

Calvino died before he finished his last memo about consistency, so you can interpret it as you like. At FoAM we see it as a consistency of process, a determination that our administrative work enables other types of work to develop and our collaborators to grow. Our contingency reserves are perhaps not stockpiles of money, food and medicine, but rather relationships, carefully cultivated over time and across continents. Relationships with people and places that give us hope.

“Hope is not a door” says Rebecca Solnit, “Hope is a sense that there might be a door at some point, some way out of the problems of the present moment even before that way is found or followed.”

With thanks to Kate Rich, The Feral Business Network, Cube Cinema and IBEX (Institute for Experiments with Business)